#Muhsin Al-Ramli

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Recommendations: On the New Wave of Memoirs from Iraq

Editor’s note: Publishers who are interested in Iraqi literatures will find more in our May Publishers Newsletter, out on May 15. By Hend Saeed In recent decades, memoir has burgeoned in prominence and popularity among Iraqi writers and readers. As acclaimed author-translator Falah Raheem tells us: “Autobiography is one of the most prolific genres in present day Iraq. Needless to say, Iraq has…

View On WordPress

#Ata Abdulwahab#Balkis Sharara#Diaa Khudair#Gardens of Faces#Inaam Kachachi#May Muzaffar#Muhsin al-Ramli#Rafa al-Nasiri#Salah Niazi#هكذا مرت الأيام#Widad Al Orfali#حدائق الوجوه#رحلتي إلى الصين#سلالة الطين#سوالف#غصن مُطَعّم بشجرة غريبة

1 note

·

View note

Text

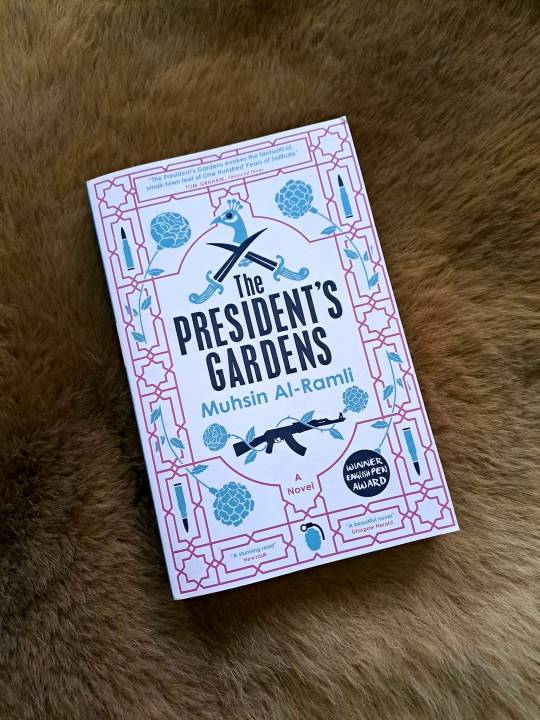

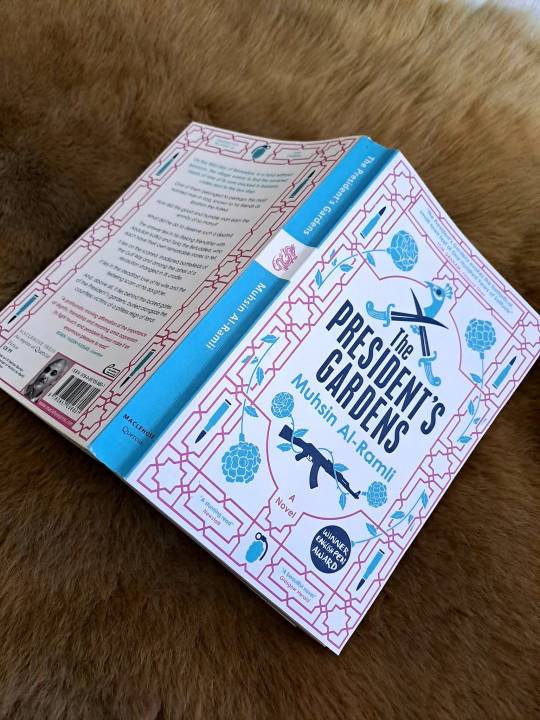

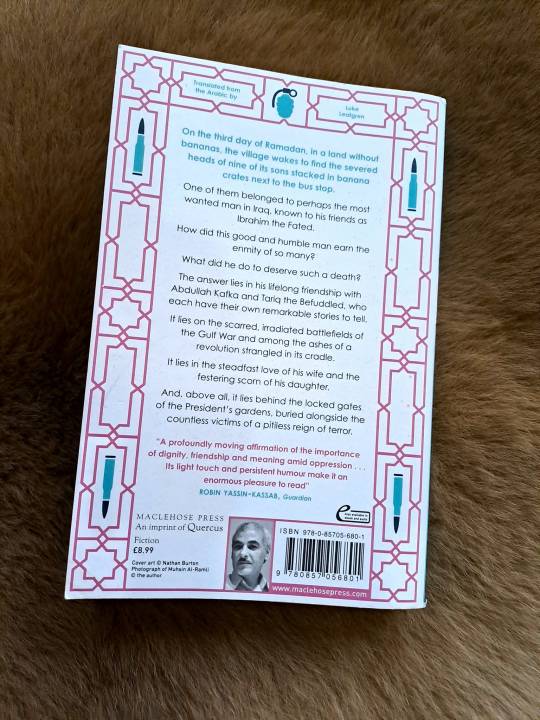

[Book Review] The President’s Garden🦚

🧮 Score: 4.9/5.0

“A Stunning Read” - Newstalk. Indeed, it is.

■ If you love the works by Khaled Hosseini, you have to read this book. If you empathise with reading “Burned Alive” and “The Stoning of M. Soraya”, you will appreciate this book.

Love, anger, compassion, cruelty and more, are the flavour of life. This book took you on a journey. A glimpse of all the major events in Iraq and of its people. Of the local family system. Of the society’s hierarchy. Of the wars in the 40s, 60s, early 90s and of the revolution in the early 2000s. These chaotic conditions were the streaming backgrounds of the characters’ lives. The book indirectly highlighted the rumours surrounding crises in the Arab world. .

■ Originally authored in Arabic by Muhsin Al-Ramli, it was well-translated by Luke Leafgren. To me, the narration is flawless. In the first few chapters, it seems like a typical Arabic style of storytelling. As we go on, the content is not all over the place. It is well structured. It is deep, but not too deep. Like the curtains of our sights were lifted one at a time. All the small details meant something.

It is thought-provoking yet, did not burden too much. Borderline is gruesome and not. Slight adult content. Well-balanced emotions-play. Everyone is the protagonist in their own lives. Then, when their lives intertwined with others, it created another main story.

■ It began with the discovery of 9 heads found in a banana crate in a small village away from Baghdad, Iraq. One of the heads belongs to Ibrahim the Fated. And the story revolves around the people close to him during his lifetime.

When the President’s Garden was first revealed, I was still cruising, at best, I suspected a few jump-scares and “over-the-top wealthiness”. After time spent in the garden, never I imagined that I would be as shocked as the character was. Unexpectedly, arriving at that one scene, my jaws literally dropped. I was stunned, that I needed a few moments before resumed my reading. And moving forward, the penmanship never stops to impress us. It is amazing how complex this novel is, yet the author manages to convey them nonchalantly. .

■ Apart from the praise-worthy penmanship, what I like about this book is that, subtly, it calls out the wrongful things people did in the name of religion. Unlike “Burned Alive”, in displaying the barbaric, uncultured, materialistic human nature, this book also clarifies that those actions have nothing to do with Islam.

One more thing, the cover design is brilliant. At one glance, it looks like a typical Middle Eastern art with a peacock and swords to boast one's wealth. When you look again, you will notice more details, the hand grenades, bullets and AK-47. Good colour scheme, too.

■ The author played with our emotions till the end of the chapter. There is a sequel to this book titled: "Daughter of the Tigris" I do not have it, yet. But I am very much looking forward to it! I know, it will be as good as this one, if not more.

--- ● Get the preloved book on Carousell. . --- *Also read other platforms:

Instagram

Facebook --- ● Follow me on Telegram for quick updates! --

#book review#Muhsin AL Ramli#The President's Garden#Arabic Novel#English Translated#Luke Leafgren#Book Review#Recommended Reading#Preloved Book#Carousell Malaysia

1 note

·

View note

Photo

From a tragicomedy from Iraq to a razor-sharp take on being a mistress, from Sweden, 5 great books you may have overlooked last month.

#Muhsin Al-Ramli#The President’s Gardens#Lena Andersson#Acts of Infidelity#Malcolm Hansen#They Come in All Colors#Casey Plett#Little Fish#Dag Solstad#T Singer#Bethanne Patrick

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Resumen segunda semana de club de lectura con Mus

Resumen segunda semana de club de lectura con Mus. Os dejamos el enlace a las grabaciones y algunos artículos bien curados por @Silvia84 sobre los temas que se abordan en la novela. #LiteraturaÁrabe #ClubDeLecturaSeparataÁrabe

El viernes día 15 de enero tuvimos la segunda sesión del club dedicada a comentar Los jardines del Presidente de Muhsin Al-Ramli, en adelante Mus para nosotros. Continue reading

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

SALAFI MASHAYKH

This is a list of SOME (NOT ALL) Salafi scholars and (senior) students of knowledge of this era (a few are dead but the majority are alive today) who resided in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Egypt, Yemen, U.A.E., Algeria, Iraq and Jordan.

A handful of the scholars on this list have been refuted by other scholars on the list on particular issues but nothing that takes them out of Salafiyyah to the best of my knowledge.

PLEASE DO NOT MESSAGE ME OR SEND ME ANY REFUTATIONS ETC TO DISSCUSS, AGRUE OR DEBATE WITH ME OVER ANY OF THE MASHAYKH ON THIS LIST BECAUSE YOU HOLD THEY ARE NOT SALAFI.

List Of Contemporary Mashaykh (Divided In To Places Of Residence Of These Mashaykh Not Places Of Birth)

Saudi Arabia

Shaykh Abdul-Azeez Aal Shaykh

Shaykh Abi Abdillah Mahir Bin Dhafer Al-Qahtani

Shaykh Alee Ridaa

Shaykh Abdul-Kareem Al-Khudair

Shaykh Mustafa Mubram

Shaykh Saalih Aal-Taalib

Shaykh Khaalid Al-Ghaamadi

Shaykh Ali Abdur-Rehmaan Al-Huthayfi

Shaykh Salaah Al-Budayr

Shaykh S’ad Naasir Ash-Shithri

Shaykh Saalih Al-Luhaydaan

Shaykh Abdul-‘Azeez Ar-Raajihi

Shaykh Abdur-Rehmaan Al-‘Ajlaan

Shaykh Abdul-Muhsin Al-Abbad

Shaykh Rabee Ibn Haadi Al-Madkhali

Shaykh Saalih Al-Ubood

Shaykh Abdullaah Al-Jarboo

Shaykh Mis’ad Al-Husayni

Shaykh Saalih As-Sindi

Shaykh Ali At-Tuwayjari

Shaykh Ibrahim Ar-Ruhayli

Shaykh Khalid Ar-Raddadi

Shaykh Sulaymaan Ar-Ruhayli

Shaykh Muhammed Al-Hujayli

Shaykh Abdullah Al-Bukhari

Shaykh Saalih As-Suhaymi

Shaykh Wasi-Ullaah Al-‘Abbas

Shaykh Abdur-Rehmaan As-Sudays

Shaykh Ghurmullaah Zahrani

Shaykh Uthmaan Mu’Allaam

Shaykh Muhammed Umar Bazmool

Shaykh Aadel As-Subayee

Shaykh Abdullaah Al-Musallam

Shaykh Fahad Al-Fuhayd

Shaykh Saalih As-Sadlaan

Shaykh Ahmed Al-Munayee

Shaykh Abdul-‘Azeez As-Saeed

Shaykh Muhammed Aadam

Shaykh Salaah Al-Budayr

Shaykh Abdul- Azeez Al-Faalih

Shaykh Salaah Muhammed Aal Shaykh

Shaykh Ahmed Bazmool

Shaykh Abdul Majeed As-Subayyal

Shaykh Muhammed Al-Munayee

Shaykh Abdul Azeez Rayyis

Shaykh Abdullah Al-Ghunaymaan

Shaykh Alee Naasir al-Faqeehee

Shaykh Dr ‘Abdul-‘Aziz al-Sadhan

Shaykh Dr Khalid al-Mushayqih

Shaykh Muhammad al Maliki

Shaykh Muhammad bin ‘Abdul-Wahhaab Al-’Aqeel

Shaykh Saalih Ibn Saalih al-Fawzaan

Shaykh Ubayd Ibn ‘Abdullaah al-Jaabiree

Shaykh ‘Uthmaan Ibn Yahya al-Hamali

Shaykh Abdul-Muhsin Al-Ubaykan

Shaykh Ubaylaan

Shaykh Abdullah Ibn Sulfeeq adh-Dhafiri

Shaykh Muhammad Ibn Haadee al-Madkhalee

Shaykh Fu’ad Ibn Sa’ud al-‘Amri

Shaykh Prof. Asim al-Qaryuti

Shaykh Dr. Adil Muhammad Subay’ee

Shaykh Haythem Sarhaan

Shaykh Abdul Qaadir Ibn Muhammad al-Junaid

Shaykh ‘Adil Mansoor

Shaykh Fawaaz al-Madkhalee

Shaykh Hani Bareek

Shaykh Muhammad Sagheer ‘Akoor al-Madkhalee

Shaykh Muhammad Ibn Ramzaan al-Haajiree

Shaykh Badr Ibn Muhammad al-Badr al-‘Anazy

Shaykh Yahya at-Taaliby

Shaykh ‘Arafat Muhammady

Shaykh Muhammad ‘Awaji al-Muhjari al Madkhalee

Shaykh Hasan Daghriry

Shaykh Usamah Ibn Sa’ud al-‘Amri

Shaykh ‘Abdul’Azeez Ibn Moosaa Ibn Sayr al-Mubaaraky

Shaykh Muhammad Ibn Rabee’ Ibn Haadee al-Madkhalee

Shaykh ‘Awaad Sabty al-‘Anazy

Shaykh Abu ‘Umar Usamah al-‘Utaybi

Shaykh Khalid Namazy

Shaykh Ahmad ‘Aloosh al-Madkhalee

Shaykh ‘Uthmaan al-Mu’alim Somali

Shaykh Saalim Baamihriz Yemeni

Shaykh Doctor ‘Abdur Razzaaq Ibn ‘Abdul Muhsin al-‘Badr

Shaykh Abdul Malik ar-Ramadani

Shaykh Nasir Alaql

Shaykh Saeed Bin Ali Bin Wahf Al-Qahtani

Shaykh Abdur Rahman Muhay Deen

Yemen

Shaykh Abdullah Ibn Naajee al-Hadaad

Shaykh Rashaad al-Hubaishi

Shaykh Abu Amr’ Abdul Kareem Ibn Ahmed Al Hajooree

Shaykh ‘Ali Ibn Naasir Al ‘Adani

Shaykh Abdul-Ghani al-Umaree

Shaykh AbdulHameed al-Hajooree

Shaykh Abu Abdis Salaam Hasan Qaasim Ar Raymee

Shaykh Fath Al-Qadsi

Shaykh Khalid Abdul Rahman Al-Misree

Shaykh Muhammad al-Hakami

Shaykh Muhammad Bin Hizam

Shaykh Abu Abdur Rahman Abdullah Airyaani

Shaykh Salaah Kentush

Shaykh Abu Razzaq Al Nehmee

Shaykh Abdul Rakeeb Al Kawkabanee

Shaykh Muhammad Al Imam

Shaykh Muhammad Ibn ‘Abdul-Wahhaab al-Wassaabee

Shaykh ‘Ali Ibn Ahmad ar-Razihi

Shaykh ‘Abdul ‘Azeez Ibn Yahya al-Bura’ee

Shaykh ‘AbdulGhafoor al��Lahaji

Shaykh ‘Abdur Rahmaan al-‘Adani

Shaykh Abu ‘Abdullah ‘Uthmaan Ibn ‘Abdullah as-Saalimee

Shaykh Abu Ammaar ‘Ali al-Hudayfee

Shaykh Abu Abdullah Uthmaan Ibn ‘Abdullah as-Saalimee

Shaykh, ‘Ali al-Qaleesee

Shaykh Ahmad Ibn Ahmad Shamlaan

Shaykh Saalim Baamihriz

Shaykh Yahyaa al-Jaabiree

Shaykh ‘Ali Ibn Ahmad ar-Razihi

Shaykh Abu Yahya Zakariyyah al-‘Adani

Shaykh ‘Abdur Rahmaan al-‘Adani

Shaykh Nu’maan al-Watr

Shaykh ‘Abdul Wasee’ as-Sa’eedi

Kuwait

Shaykh Ahmed al-Subai

Shaykh Abdullah Shreikah

Shaykh Faisal al Jaasim

Shaykh Falaah Ismaa’eel al-Mundikaar

Shaykh Falah al-Thani

Shaykh Hai Al Hai

Shaykh Hamd Al Uthman

Shaykh Hamdi Abdul Majeed

Shaykh Hamoud al-Najdi

Shaykh Mohammed al-Anjaree

Shaykh Saalim Taweel

Egypt

Shaykh Muhammad Abdul Wahhaab Al-Banna

Shaykh Khalid Abdul Rahman Al-Misree

Shaykh Khalid Bin Uthmaan

Shaykh Adil As’Sayyid

Shaykh Aadl Shoorbojee

Shaykh Talaat

Shaykh Raslaan

Shaykh Hasan ibn ‘Abdul Wahhab al-Banna

Shaykh Ali al-Waseefi

Shaykh Taamir Fatooh

Jordan

Shaykh Abu Islam

Shaykh Mohammed Musa Nasr

Shaykh Husain al-A’waiyashah

Shaykh Aba al-Hasan ‘Ali Ibn Mukhtar ar-Ramly

Shaykh Mashoor Hasan

Shaykh Sa’ad al-Husayn

U.A.E.

Shaykh Haamid Ibn Khamees al-Junaybi

Shaykh Ahmad Ibn Mubarak al-Mazroo’i

Iraq

Shaykh Mowafaq Hussein al-Jaboory

Shaykh Abu ‘Abdul Haqq ‘Abdul Lateef al-Kurdi

Algeria

Shaykh Azhar Sniqra

Shaykh Muhammad Ferkous

Shaykh Yusuf Al-Jazaa’iree

(A Few Mashaykh Who Died In This Era)

Shaykh Muqbil

Shaykh Uthaymeen

Shaykh Bin Baz

Shaykh Albaani

Shaykh Shaykh Abdus-Salam Bin Burjis

Shaykh Dr Saleh Al-Saleh

Shaykh Muhammad Ibn ‘Abdullaah As-Subayyal

Shaykh Zayd Ibn Haadee al-Madkhalee

Shaykh Abdullah An-Najmee

Shaykh ‘Abdur-Razzaaq Ibn ‘Afeefee

Shaykh Bakar ‘Abdullaah Abu Zayd

Shaykh Abdullaah al-Ghudayyaan

Inshallah this list will get updated from time to time.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Los jardines del presidente", de Muhsin Al-Ramli

“Los jardines del presidente”, de Muhsin Al-Ramli

Muhsin Al-Ramli ganador del English Pen Award «La novela de Muhsin Al-Ramli, ‘Los jardines del presidente’, ofrece una visión increíble de la vida iraquí.» .

«En el tercer día de Ramadán de 2006, en un país sin platanares, los habitantes del pueblo se despertaron con la llegada de nueve cajas para transportar plátanos. En cada una de ellas estaban depositados la cabeza degollada de uno de sus…

View On WordPress

#Alianza Editorial#Íñigo Sánchez-Paños#Colección Alianza Literaria (AL)#Elena M. Cano#Had-a&039;iq ar-ra&039;ays#Los jardines del presidente#Muhsin Al-Ramli#Nehad Bebars#محسن الرملي#حدائق الرئيس

0 notes

Text

Review: The President's Garden by Muhsin Al-Ramli

Review: The President’s Garden by Muhsin Al-Ramli

On the morning of the third day of Ramadan, a village in Iraq wakes to find the heads of nine of its men stacked in banana crates by the bus stop. One of them, known to his friends as Ibrahim the Fated, is one of the most wanted men in Iraq. From the village of his birth through three wars and the lives of his best friends, The President’s Gardenstells the story of how Ibrahim earned the enmity…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Book 29, 2019: 'The President's Gardens' by Muhsin Al-Ramli.

Iraq. Village living. City life. Three friends. Family. Secret. Saddam Hussein. Gulf War. Iran. The Invasion. Oppression. Terror. Generational stories.

Weltanschauung!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

If you scour the internet for Iraqi novels, you’ll find dozens of lists and list-essays. But these pieces—15 Great Books About Iraq, Afghanistan or The Iraq Novel We’ve Been Waiting For or I’m Not the Enemy or A Reading List of Modern War Stories—give us the perspective of the US soldier, journalist, and aid worker.

What they tell us very little about is Iraq.

Two years after the invasion, in 2005, USA Today reported that more than 300 books had been published in English about the war and ongoing occupation. By now, an Amazon search turns up more than 3,800. A number of them have been critically and commercially successful: American Sniper, The Final Move Beyond Iraq, War Stories, Redeployment, Yellow Birds.

Yet in the first ten years after the invasion, exceptionally few novels by Iraqi authors had been published in English.

That has been changing. This year, we saw the publication of Muhsin al-Ramli’s The President’s Gardens, translated by Luke Leafgren; the sci-fi collection Iraq + 100, edited by Hassan Blasim and Ra Page; and Baghdad Eucharist, by Sinan Antoon, translated by Maia Tabet. There are novels by Iraqi authors now. Here’s some of the best.

https://bookriot.com/2017/11/08/2018-novels-by-iraqi-authors/

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Books: Recommendations from Bothayna al-Essa

5 Books: Recommendations from Bothayna al-Essa

Best-selling and award-winning Kuwaiti novelist Bothayna Al-Essa — also the founder of Takween, a platform for creative writing, a publishing house, and a bookshop — is a voracious reader:

Al-Essa published her first novel (Soundless Collision) at 23, and she has since published more than ten books for adults and children. Her first novel to appear in English translation arrived this spring:…

View On WordPress

#A City of Walls without End#Dalia Tounsi#Faisal al-Habini#he Pigeons’ House#Island of Leaves#Muhsin al-Ramli#Saud Al-Sanousi#Scattered Crumbs#Sons of the End Times#Tariq Imam

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

Resumen primera semana y sesión sobre Los jardines del presidente de Muhsin Al-Ramli

Resumen primera semana y sesión sobre Los jardines del presidente de Muhsin Al-Ramli. Para quienes no podéis asistir pero estáis interesados en leer esta obra. @Silvia84 y yo, esperamos que te sea útil. #ClubDeLecturaSeparataÁrabe

Por Silvia R. Taberné y Maribel Glez Martínez El pasado viernes, 8 de enero, tuvimos la primera sesión para comentar e intercambiar impresiones sobre la lectura de Los jardines del Presidente de Muhsin Al-Ramli. La gran sorpresa fue que el mismo autor también participa en estas sesiones. Por eso, si no lo has hecho todavía, te animamos a que te unas a esta aventura. Desde que resultase vencedor…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Gatot Nurmantyo, Din Syamsuddin, Dan Rochmat Wahab Sampaikan Pesan Presidium, Begini Susunan Acara Deklarasi KAMI

Ratusan tokoh akan hadir di acara deklarasi maklumat Koalisi Aksi Menyelamatkan Indonesia (KAMI) di Tugu Proklamasi, Jakarta Pusat pada Selasa (18/8) siang ini. Acara deklarasi maklumat KAMI akan berlangsung pada pukul 10.00 hingga pukul 12.00. Pada acara tersebut, sejumlah tokoh akan membacakan delapan poin maklumat KAMI hingga penyampaian pesan presidium KAMI oleh mantan Panglima TNI, Jenderal (Purn) TNI Gatot Nurmantyo; pemimpin Komite Khittah Nahdlatul Ulama 1926, Prof Rochmat Wahab; dan Ketua Dewan Pertimbangan Majelis Ulama Indonesia (MUI), Din Syamsuddin. Dalam susunan acara yang diterima Kantor Berita Politik RMOL, acara tersebut diawali dengan registrasi peserta dan pemutaran lagu-lagu perjuangan sejak pukul 09.00 hingga 10.00. Selanjutnya pada pukul 10.00, acara dibuka oleh MC, yakni Najamudin Ramli dan Dinda Kartika dan dilanjutkan doa oleh KH Agus Solahul Am Wahib Wahab selalu Sekretaris Jenderal Komite Khittah NU 1926. Kemudian, menyanyikan lagu Indonesia Raya yang dipimpin oleh Prof Sri Edi Swasono sebagai dirigen dengan diiringi paduan suara. Selanjutnya mengheningkan cipta yang dipimpin oleh Bahtiar Chamsyah selaku Ketua Lansia Nasional. Selanjutnya pembacaan Teks Proklamasi yang dipimpin oleh Prof Meutia Farida Hatta Swasono yang merupakan putri proklamator Bung Hatta. Kemudian, pembacaan pembukaan UUD 1945 oleh Sabriati Aziz selaku Presidium Badan Musyawarah Organisasi Wanita Islam; Nur Eko selaku Koordinator BEM Perguruan Tinggi Muhammadiyah se-Indonesia; dan Batara Hutagalung. Selanjutnya pembacaan Teks Pancasila oleh M.S Ka'ban yang diikuti oleh seluruh hadirin. Dan dilanjutkan menyanyikan lagu-lagu perjuangan. Seperti Gebyar-gebyar dan Padamu Negeri oleh paduan suara. Kemudian memasuki acara inti deklarasi KAMI, yakni deklarasi menyelamatkan Indonesia sebagai pertanda pendirian KAMI dengan didahului pembacaan Jatidir KAMI oleh Dr. Ahmad Yani. Selanjutnya, pembacaan maklumat menyelamatkan Indonesia yang dibacakan secara bergantian oleh beberapa tokoh. Diantaranya, Marfuah Mustofa, Raja Samu-samu, Prof Hafid Abbas, Ichsanuddin Noorsy, Lieus Sungkharisma, Nurhayati Assegaf, Chusnul Mariyah, Jumhur Hidayat. Dan Budi Jatmiko, Jeje Jaenuddin, Adhie Massardi, Dian Fatwa, Marwan Batubara, Nanang Mubarok, Abdullah Hehamahua, Said Didu, Ilham Bintang, Refly Harun, Syahganda Nainggolan, Muhsin Al-Attas dan Rocky Gerung. Di akhir acara, tiga tokoh diantaranya yakni Gatot Nurmantyo, Rochmad Wahab dan Din Syamsuddin akan menyampaikan pesan presidium KAMI dan dilanjutkan dengan penutup yang diiringi lagu-lagu kebangsaan. from Blogger https://ift.tt/320Z5Wf via IFTTT

0 notes

Text

Spotlight | Read the World with MacLehose Press | 5 Notable Writers

Spotlight | Read the World with MacLehose Press | 5 Notable Writers

Luke Leafgren, the translator of Muhsin al-Ramli’s The President’s Gardens (MacLehose Press) will receive the 2018 Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation on Wednesday 13 February. The awards and the ceremony are administered, organised and hosted by the Society of Authors.

As small-island mentality tightens its hold on the UK, and the dark forces of obsessive fear-mongering…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

«Los iraquíes han reaccionado contra el fanatismo por el Daesh, y ahora dicen ser laicos»

«Los iraquíes han reaccionado contra el fanatismo por el Daesh, y ahora dicen ser laicos»

«Anteriormente la cultura árabe tenía prohibido escribir sobre tres temas: política, religión y sexo. Hoy en día podemos escribir de lo que queramos, en algunos países hay censura oficial, pero en la mayoría lo que prevalece es una suerte de censura colectiva», sostiene a ABC el escritor iraquí Muhsin al Ramli (Irak, 1967). Exiliado en España desde 1995 después de que su hermano (Hassan Mutlak)…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Link

“ALL IRAQIS WILL READILY agree that their life has always been noir,” says editor Samuel Shimon in his introduction to Baghdad Noir, one of the two latest volumes in Akashic Books’s globe-spanning “Noir” series (the other being Marrakech Noir, edited by Yassin Adnan and released on the same day, although covering cities at the opposite ends of the Arab world). But while the oppression and violence that have marked Iraq’s recent history furnish plenty of grimness for the mood associated with noir fiction and film, the genre is distinctly American in origin, from black-and-white Hollywood movies of sin and betrayal to Philip Marlowe’s jaded outlook on human nature. As Shimon points out in his introduction, the Iraqi authors he approached were less directly familiar with the genre, and Baghdad Noir is the first collection of Iraqi crime fiction that he is aware of. [1] So, tasked with commissioning the 14 stories included in this volume, he arranged to translate into Arabic a story by the late Maggie Estep that was published in Akashic’s early Queens Noir collection, and sent the translation to the writers as a model of noir style to follow.

As a result, the contributors have found ways to make this genre their own. What is surprising here is the breadth of settings and eras for these stories, ranging from 1950, during the relatively stable period of the Hashemite monarchy, through the paranoid years of Ba’athist rule, the sanctions era of the 1990s, and the violent years after 2003, up to the more recent threat of terrorism embodied by Daesh’s (ISIS) draconian rule over Iraq’s north.

Ten of the authors represented here are Iraqi; the other four are American, Iranian, Tunisian, and Lebanese. Shimon has managed to secure stories from some of the most prominent Iraqi authors now writing, such as Ahmed Saadawi, Sinan Antoon, Muhsin al-Ramli, and Ali Bader. Of the four women writers in the book, only two are Iraqi: it would have been interesting to see prominent Iraqi women writers like Inaam Kachachi or Dunya Mikhail try their hand at noir. I was unfamiliar with several of these contributors, and it speaks to their talents that these stories piqued my interest to track down their full-length novels.

Noir is a broad category — it may refer primarily to a story’s general mood, or it can refer to specific plot elements. For this collection, some of the contributors wrote their noir as stories of murder and the search for a killer. Muhsin al-Ramli, perhaps best known for his 2012 novel Hada’iq al-Ra’is (published in English as The President’s Gardens), opens the collection with a whodunit set in an apartment building in Baghdad during the American occupation. It begins with the discovery of a murdered young woman in the courtyard of the building, which has been locked down after the night’s curfew. It’s a classic closed environment as the house’s occupants eye each other warily, knowing that the killer must be among them. Al-Ramli has a flair for evoking urban squalor (the neighborhood carries “smoke from piles of putrid, smoldering garbage mixed with the scent of grilled meat and spices”) and corruption (the police are “good for nothing except taking bribes”), while the story peels back the layers of lust, politics, and mixed motives that lead to murder.

The Iraqi authorities in general, and Baghdad’s police specifically, don’t come off well in this collection, being either ineffectual or actively criminal, as in Mohammed Alwan Jabr’s compelling “Room 22,” a tense account of a man bringing a suitcase full of ransom money to a hotel room in order to pay off his young nephew’s kidnappers, only to discover a greater web of religious and official corruption behind the abduction. One exception to this dim view of law enforcement is Salima Salih’s compact “The Apartment,” in which a dogged police inspector, Naji Nassar, investigates the brutal murder of an old lady at her home. Even here, though, the story closes not on the arrest of the guilty party, but just a world-weary acknowledgment that this is “just another day in Baghdad.”

The identity of the killer is more elusive in the excellent “Empty Bottles” by novelist Hussain al-Mozany, who died shortly after completing this story. Set in the 1950s working-class neighborhood of al-Thawra City (now since renamed Sadr City), it begins with a gruesome “honor killing” committed at dawn, witnessed by the 12-year-old narrator’s mother. The killing becomes an obsession with al-Mozany’s narrator, who comes to a disturbing realization about why honor killings are so prevalent among the poor: “A feeling struck me like a thunderbolt that honor was the only wealth the poor had…” In his morbid imagination, the killer transforms into a monster of folklore, a djinn known as the tantal that kidnaps children in the night. Al-Mozany’s story focuses our attention on the ongoing impact of violence, rippling out from the past in unexpected ways. The narrator didn’t even witness the murder himself, but it becomes a permanent rupture in his later life, making him, as he says, “an indirect victim of its savagery.”

Another standout in this collection is Ali Bader’s “Baghdad House,” which is set in 1950 and features a middle-class, educated protagonist. The story’s milieu is vastly different from the rest of the book, given the political and social changes Iraq has witnessed since 1950 — the overthrow of the monarchy in the late 1950s, the subsequent political assassinations and coups culminating in the Ba’athist coup in 1968, followed by the ascendancy of Saddam (itself a kind of internal coup), and the years of war, sanctions, and occupation that followed. In Bader’s contribution, an accountant for an automotive company is temporarily transferred from Basra to the company’s Baghdad office to replace two colleagues who have successively gone missing. Both of his vanished predecessors had been residents at the same upscale lodging house, Baghdad House, where he, too, is assigned to stay. On his first day there, one of its longtime residents, a Persian woman, is murdered, and the accountant finds himself becoming a detective, uncovering a sordid demimonde of upper-crust Baghdad. Even more than others in this collection, this narrative — a clear homage to Agatha Christie’s mysteries — seems like a novel in miniature that could easily have been expanded. Bader has already proven himself adept with historical settings, and if he ever chose to write a full-length mystery novel set in 1950s Baghdad, I would jump at the chance to read it.

Noir can also draw on the darker recesses of human psychology, on madness and unreliable narrators that pull the rug out from under the reader. Of the stories that took that route, the foremost is Sinan Antoon’s excellent “Jasim’s File,” which is based on a true incident involving the mass escape of mental patients from Baghdad’s al-Rashad Hospital when the Americans invaded. “The Americans kind of liberated me,” says the protagonist, Jasim, as he flees the mental ward and returns to his family home during the chaos of April 2003. Living in his family’s empty home, Jasim falls into working with a friend who has joined the Badr Brigade, a military faction formed by Iran during the Iran-Iraq War, with the express purpose of encouraging an Iranian-style Islamic revolution in Iraq. The story concludes with an ironic reveal after we have learned that Jasim has graduated to assassinations. Jasim’s story replays in miniature the devastation of the 2003 occupation that gave free rein to social disorder and allowed criminal behavior to drift easily into terrorism.

Dheya al-Khalidi’s “Getting to Abu Nuwas Street” has a great noir opening, one that wouldn’t seem out of place in a Chandler novel (“I come to in the morning, and see that I’m in an abandoned metal shop. Tied up.”). Al-Khalidi’s 2012 novel al-Qutla (The Killers) is set during the violent years after 2003, and this kicker of a story conveys some of the same flavor, but featuring a narrator with fuzzy memories of the events that led to his capture. The American troops may have withdrawn in 2009, but Baghdad’s violence remains: “American soldiers used to command Baghdad’s nights — their Humvees roaring, keeping us awake and afraid. Then the night’s custody switched over to our Iraqi brownness — bullets flying freely — even for a riled cat or a hungry dog.” Here, nighttime Baghdad has a particular menace, a city strangely desolate of humans after curfew and shrouded in blackness. The story is saturated with the narrator’s memories — such as his nostalgia for happier times, which led him to break curfew to try and reach Abu Nuwas park the night before — even though memory itself, like the titular park the narrator can never reach, becomes elusive, slippery, and leading to danger.

“Post-Traumatic Stress Reality in Qadisiya,” by the Lebanese-born author Hadia Said, concerns an increasingly paranoid protagonist, Amin, who is looking to regain the right to his family’s long-abandoned home in the Qadisiya district. He is desperate to find the title deed and key to the house, which his dying grandmother had given to him. The story veers between Amin’s memories of the past and his hallucinatory present reality. The spectral appearance of long-dead family members makes this a ghost story — particularly given the ending, which suggests that Amin himself may be the one who is dead and buried.

Two stories revolve around the noirish trope of characters with a death wish, fueled by regrets about their own past crimes. The first is “A Sense of Remorse” by Ahmed Saadawi — best known to English-language readers for his novel Frankenstein in Baghdad, a finalist for the 2018 Man Booker International Prize — in which a police investigator looks into the mysterious death of his alcoholic older brother. His brother’s suicide leads him to uncover his brother’s Ba’athist past, a charlatan who once made amulets that claimed to help recruits escape military service, and a poison that only kills those who are incapable of feeling remorse. The revelations about the brother offer a disturbing insight into the way power corrupts and gives license to cruelty:

I want to feel remorse […] to cry about the terrible things I did, but it looks like I’m hopeless. I’m a demon, and I’ll admit to you right now that I enjoyed doing what I did. It was fun. It gave me an amazing sense of power and control. Is that what a normal person would say?

Salar Abdoh’s “Baghdad on Borrowed Time” also features a character with a death wish. Of all the stories in the collection, Abdoh’s hews most closely to the tropes of traditional noir and explicitly references American noir fiction. The protagonist is a Tehran-based private investigator whose clients always insist on bringing up Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler with him. This Iranian PI — who was once a POW held by Iraq — is hired by an Iraqi client who wants him to find a killer (“a serial killer with a purpose”) who has murdered a string of middle-aged men in Baghdad. The client, as we learn, is a veteran of the Badr Brigade, who lived for years in exile in Iran and only returned to Iraq after 2003.

Each of the victims is a former Iraqi soldier who had spent time occupying part of Iran. The murderer is somehow tracking down the former soldiers and taking three-decades-old revenge on people who are otherwise strangers to him. The investigator realizes he is being asked to solve murders that no one cares about, in a city already teeming with violence and bloodshed, for a client with no seeming connection to the crime. In a twist, the culprit begs the investigator to catch him and then brings him along to witness his final murder and his suicide, all in time for the investigator to catch his midnight flight back home to Tehran. As with Saadawi’s story, a character’s grief dates back to the Iran-Iraq War, a pointed reminder of the impact that that prolonged conflict had on the people of both countries, long before Operation Iraqi Freedom was a glint in Dick Cheney’s eye.

Two other authors, Layla Qasrany and Hayet Raies, mine the climate of paranoia that characterized Ba’athist Iraq for their stories, which are both set in the late 1970s. Hayet Raies was born in Tunisia but did her master’s degree at Baghdad University, an experience that informs the tense setting of “The Fear of Iraqi Intelligence,” as a female university student negotiates the disappearance of her roommate. The palpable presence of the authoritarian state is unmistakable, and Raies effectively conveys the fear it invoked, such as students monitoring their private dorm-room conversations lest their closest friends turn out to be government informers. The atmosphere is stifling even for relatively privileged foreign students, and even if Raies’s story doesn’t exactly seem noir, it makes for a compelling read. Likewise, Layla Qasrany’s “Tuesday of Sorrows” depicts an educated, middle-class family attempting to emigrate from Iraq without arousing the suspicions of the Ba’athist authorities. The atmosphere is claustrophobic, and these characters, too, use private code words to fool eavesdroppers. On the day of their departure to London, a man with an axe bursts into the apartment and kills the mother, a symbol of the state’s unchecked power over people’s lives, and its ability to wreak havoc for reasons of its own.

Two final stories are linked by their focus on protagonists taking revenge. Unlike the other stories, where the protagonists are victims, or at best witnesses to evil, in these two stories, the protagonists commit murder themselves. Roy Scranton’s “Homecoming” is a neatly plotted tale of a son’s vengeance against local thugs in Baghdad. I initially felt that the inclusion of an American author was unnecessary — after all, there are plenty of novels and memoirs written by Americans about Iraq post-2003, and far too few works of fiction by Iraqis made available to English-language readers. However, Scranton, who had previously been a soldier in the US army in Iraq in 2003 and 2004 and has since become an essayist and teacher of creative writing, has more than justified his placement in this collection with this lived-in tale, set before Mosul fell to Daesh in 2014. The protagonist, Haider, is on leave from the Iraqi army after he is injured fighting against Daesh. As always, readers may raise questions of representation, as an American author assumes the voice of a young Iraqi man, but Scranton’s story makes for a gripping read, as Haider avenges a brutal punishment meted out to his father by local thugs. It is perhaps unsurprising that there is an American character involved — albeit a distinctly unsympathetic one. As with a few other stories in this collection, “Homecoming” was written originally in English, and as such, there is a tendency for the characters to sound very much like American grunts with their fluent English swearing. The story offers a satisfying closure, but it did prompt me to wonder about the fiction yet to be written by Iraqis who lived through the most recent war against Daesh: there are surely memoirs and novels about those experiences being written now, just as the long Iran-Iraq War spawned a number of works of fiction in both Persian and Arabic.

In Nassif Falak’s “Doomsday Book,” set during the sanctions era, the narrator shadows his brother across Baghdad to discover why he is stealing items from their family home, only to discover that his brother is working for a local al-Qaeda cell. Later, after his brother disappears, the protagonist returns to the home of the cell leader and strangles him with wire. He also gets his hands on the leader’s ledger (“the doomsday book” of the title) that suggests that his brother has traveled to Afghanistan. The protagonist has some political secrets of his own, as a friend of his, just before being arrested, passed off to him a hand grenade for safekeeping, which the protagonist then buried in the yard of his house. The recurring image of the buried hand grenade, with its pin gradually rotting away, is a perfect symbol of the tensions buried within Iraqi society under Saddam, just waiting to explode into the open.

In his introduction, Shimon notes that a prominent theme in Baghdad Noir is family, and particularly the fraying of family bonds as siblings and relatives turn on each other and traditional ties loosen. I would argue, though, that the true common theme in these stories — a theme very much in the spirit of noir — is betrayal. Characters in this collection are frequently on the receiving end of unpleasant epiphanies. And as this engaging group of stories amply demonstrates, betrayal — whether by authorities, religious leaders, neighbors, colleagues, or liberators — is a subject that Iraqis know all too well.

¤

Chip Rossetti is a book editor and a translator of modern Arabic fiction.

¤

[1] Although there are certainly urban noir and noir-adjacent elements in Iraqi fiction and popular culture: I am thinking in particular of Hassan Blasim’s macabre short stories, and, more distantly, Iraqi television shows like Night Wolves (Dhi’ab al-Layl), which aired in the late 1980s, about violent gangsters in Baghdad’s criminal underworld.

The post Indirect Victims of Savagery appeared first on Los Angeles Review of Books.

from Los Angeles Review of Books https://ift.tt/2QZjDaP

0 notes